Shaping the Future Workforce – Dennis Dio Parker

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]WorkingNation consultant and workforce reporter Ramona Schindelheim reports on the innovative solutions for developing skilled workers for 21st-century jobs. Schindelheim interviewed Toyota Motors North America’s Dennis Dio Parker, whom director Barbara Kopple featured in WorkingNation’s FutureWork series. Parker is the developer of Advanced Manufacturing Career Pathways programs, which provide advanced skills training.

Even before the jobs skills crisis became a part of our everyday economic conversation, Toyota Motors North America began developing ways to keep its workforce up-to-date and competitive.

“We’ve been at it for 30 years. Within our corporate culture are the concepts of problem-solving and continuous improvement,” explains Dennis Dio Parker. He’s the man in charge of Toyota Motors North America’s ongoing process of finding and training the high-skilled workers that keep the assembly lines at its nine U.S. plants running.

Early on, Toyota saw how advances in technology were changing the automotive industry and took a proactive approach.

“Anybody working down here at this ground level knows what’s happening. We actually began developing the first training program back in late 1987, and we have been working on it ever since,” says Parker, whose official title is Assistant Manager, Toyota North American Production Support Center.

He helped found and develop the company’s most-recent program—Advanced Manufacturing Technicians (AMT)—which has graduated thousands of high-skilled workers and has captured the attention of the entire advanced manufacturing industry seeking to solve its workforce problems.

It’s an oft-repeated concern in the business world these days: there are not enough workers skilled in the trades that are needed in advanced manufacturing—engineering, computers, robotics, machining, welding and more. Some of it is due to lack of training, some due to an aging workforce.

Parker points to the well-known Deloitte studies showing that manufacturing companies have 600,000 jobs just sitting there empty because there are not enough people to fill them, and forecasting that the gap will grow to 2,000,000 by 2025.

“I think maybe one of the biggest misperceptions out there is that technology is taking away jobs. And what it’s really doing is transforming the jobs,” says Parker. “Go into almost any automotive plant, Toyota or anybody else, and you see lots of very high levels of technology. You see robots, you see vision systems, you see significantly broad aspects of how we use programming,” Parker says. “Whether you’re programming a computer, programming a logic controller, a controller for a robot, whatever, it requires a degree of human capability in order to make the operation run effectively and efficiently.”

“It turns out that these new jobs require greater training, more knowledge, higher skills for understanding than the other jobs did. As the world continues to advance and move further along, what people need to know, and do, and be capable of, is growing also,” says Parker, who describes the skills gap as a profound industry problem.

“How do we get capable people to keep up with the need for capability? We realized doing what we already did, but just trying to do it a little better, would not work,” according to Parker. “We defined what we really wanted, and that was a huge change in the American education system. You’ve got to approach it as a career pathway where you’re guiding people the whole way.”

Toyota decided the radical solution was a talent development approach that gave young workers all the skills they needed to hit the ground running. Seven years ago, AMT, an intensive, two-year program that combines classroom and lab work, with paid on-the-job training, was born.

What started out as a Toyota-only initiative now has more than 300 companies participating in nine states, partnering with 22 community/technical colleges and three universities. The collaborative of companies works together under an umbrella group they call FAME, the Federation for Advanced Manufacturing Education.

“It turns out that our problems are not unique to us by any stretch of the imagination. They’re common, really, to any employer of technical talent. 3M makes Post-It notes, makes tape. Down the road from us here in Kentucky is GE Appliances. You go beyond manufacturing and you have companies that also need employees with technical talent—L’Oréal Cosmetics, Jack Daniels, Purdue Farms,” says Parker.

Parker also lists two public utilities and a pharmaceutical company among that partner list. “They all need skilled technicians.”

AMT’s first step in recruiting students is visiting middle schools and high schools, promoting STEM and touting the advantages of entering the career path program, from tuition cost to a quicker entry into the workforce, to job satisfaction.

Parker acknowledges that manufacturing can be a tough sell to students, especially those who have math and science skills.

“If you’ve got a really capable student, especially one who has an orientation towards STEM, and they express an interest in pursuing a trade that’s based on a two-year program, or they express interest in going to a community college instead of a university, everybody’s horrified,” says Parker.

He says parents, teachers, and counselors argue to their children and students that they are “better than that. More capable than that. That (manufacturing) wouldn’t be challenging to them. We have a national misperception that really smart students are not the right students for technology. The perceptions we have in how people choose what they do, or encourage others to do—which are based in old manufacturing—contribute to that job skills gap,” according to Parker.

He says the secret weapon in getting those smart and capable students to apply for the program is bringing a sponsoring employer in on the frontline recruiting process. “Students will not listen to a two-year college recruiter. But, when employers walk into the classroom or an open house and they’re talking about real careers and real jobs, we find that suddenly the attention changes. Kids start to listen. Kids open their minds up to at least considering this. There’s no substitute for that.”

Once accepted into the program, the students immediately start learning the skills needed to get a high-tech job. “We’ve basically got every day of their learning life planned for them for the next two years—eight-plus hours a day, five days a week, five straight semesters. It’s two days at school alternating with three days at work. We achieve maximum impact with that,” says Parker.

Tuition for the program depends on which of the community college or university partner that the student enrolls through, but averages about $10,000. The students earn as much as $40,000 as a paid intern over the two years, making it possible, with planning, to graduate without college debt. “We’re very aware, right up front, that if we make this a program where you graduate debt-free, that’s gonna be very powerful when you go in and talk to a group of students.”

And while it’s not guaranteed, many of the graduates end up working for their sponsoring company, earning an annual starting salary of $64,000, plus benefits. “Over 90% of the graduates will actually employ with their original sponsoring company,” explains Parker. “The AMT graduate is so far ahead of the regular graduates.

Parker is proud of the caliber of student that AMT is now attracting. “It’s a career pathway program. Many of our students almost certainly would have applied to engineering school had they not come to AMT. And they had an initial intent of coming to AMT because they thought it would make them a better engineer. Their intent was to go to AMT, and then at the end of the two years, to go on to engineering school.”

Out of the five graduating classes, so far, only three graduates expressed any interest in continuing to an engineering program, according to Parker. “They’re making this decision voluntarily; the apple is put in front of and they’re saying, you know what, this rocks. They like it so much that they are gonna make the decision to continue in that pathway rather than to do what had originally planned to do, which had been to go into engineering. A lot of national educators think it’s the best two-year program, the best career pathway program in the U.S.”

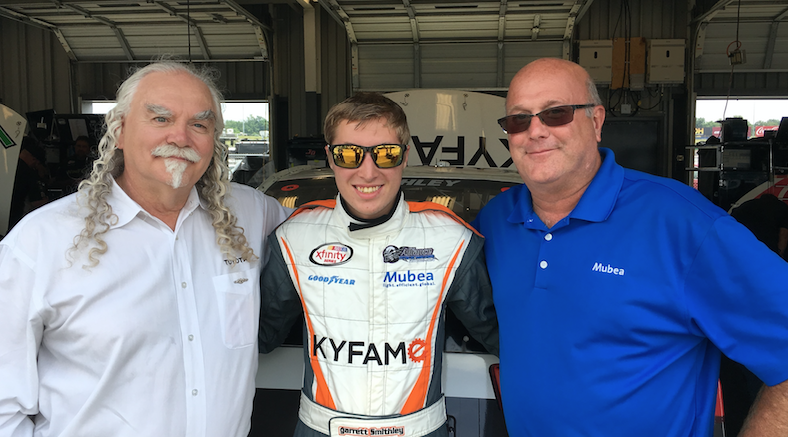

For more on the Kentucky chapter of FAME: click here.

Read full story at Working Nation[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]